Would I get a tattoo?

I don’t have a specific thing in mind, but the concept is an interesting one: can I come up with a design that I’d like to apply to my body? Something that I can’t change, at least not at all easily? That’s a tough one… as a designer I’m used to thinking and rethinking graphics, revising things that start to feel tired or dated. For this, I will clearly need to do some careful planning ahead.

The history of tattoos is as strange as it is universal. They have been made in practically every culture around the world; they’re native to almost everywhere, if you go back far enough. Ancient Celts were known to tattoo their faces and bodies, something to do with protection from evil spirits and to help in battles. There are curious parallels between Celtic and Maori body art designs. (And clear differences too, before anyone’s Fortean mystery radar kicks in.) Romans used tattooing for more practical, authoritarian ends, including marking slaves with “tax paid” when exported, and identifying soldiers on the hand to make deserters easier to find.

A sixth-century Roman doctor, Aetius, left us with a recipe for tattoo ink and basic instructions for use – although actually please don’t. It’s pretty simple, although slightly exotic: take a pound of Egyptian pine wood bark, two ounces of corroded bronze that’s been ground with vinegar, two ounces of gall, and one ounce of vitriol. Mix, sift, then soak in two parts water and one part leek juice to make the ink. Wash the skin with some more leek juice, prick the design with needles until blood is drawn, then rub in the ink. Then, presumably, cross your fingers and pray you don’t get septicemia.

That’s not the most tempting sounding mixture, but it’s the same general principle that is used today; pigment that provides the visible component, and a carrier medium. In brief, tattoos work by putting pigment particles into the dermis layer of skin. Whatever the process – injecting ink into the skin, rubbing coal dust or charcoal into cuts, even stabbing yourself with a pencil – the effect is the same: if the visible particles are deep enough in the skin and are too large for the body’s natural healing process to deal with, they remain there more or less forever.

But what design would you have? I’m assuming you’re a designer so you’d want to have the final word on the image. Sometimes tattoos are simply selected from a catalogue, maybe with a word changed here or there. A designer I was discussing tattoos with called this the Argos approach; the antithesis of original creative artwork. But any good tattoo artist will prefer to use those as idea and conversation starters rather than simple shopping catalogues.

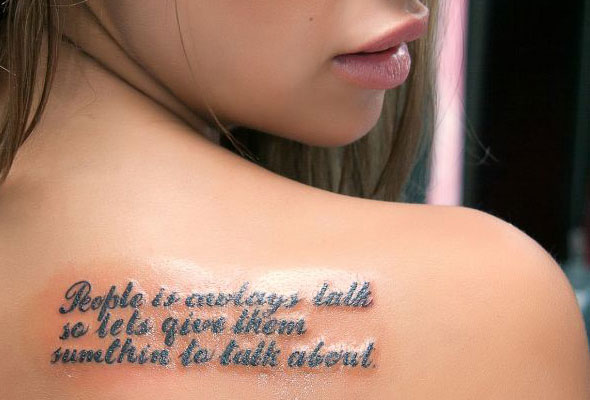

Being a type obsessive, I’m naturally drawn to something text-based. But there’s a real danger involved with tattooing words. This is something I’ve hit myself when doing signwriting and similar large lettering productions. When you’re focused intently on the shapes of each individual character in a word, one by one, it’s scarily easy to get things wrong; not seeing the word for the tees, as it were. It’s probably this more than illiteracy that’s the real culprit for most tattoo typos, but there are some lip-bitingly funny examples of mistakes online. For example, Aleksandra Nakova, a model from Macedonia, has been seen recently with a tattoo that’s a Lady Gaga quote, more or less. But instead of beginning with “People will always talk”, it says “People is awlays talk”. Other tat-oops examples from different places include “You Only Life Once” and “Black Sabbaht”. The moral of the story is simple: proof everything before you get inked, and be confident in whoever’s doing the work.

At a personal level, the most interesting tattoo I’ve seen was a friend’s design based on Marc Chagall’s angel imagery. The ‘fat angel’ was first isolated as a photocopy from a Chagall painting and given to the tattoo artist, who traced it out for approval before applying the needle.

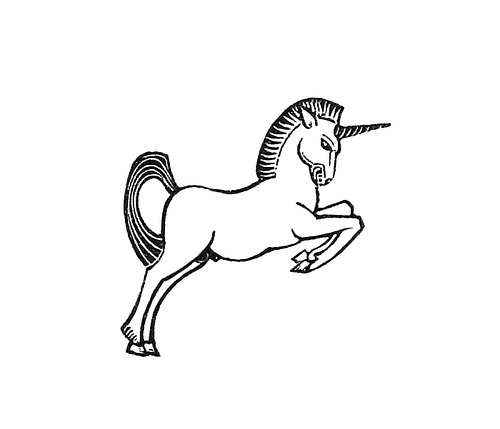

Part of the trick of making something work well in this kind of reproduction is a careful simplification of the elements. Using another of Chagall’s angels [1], this shows a two-step process that first involves [2] isolating the core of the illustration from the complete painting and rendering it in plain black and white, then [3] simplifying the ragged edges and splattered dots into confident, carefully-placed strokes. When you’re doing this don’t forget to plan for age; the pigment tends to spread slightly over the years, blurring fine detail.

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

|

|

|

Eric Gill’s illustrations are another potential source of inspiration. Both his engravings and his sturdier woodcuts show an amazing mastery of line and understanding of form, drawn with a distinctive style that is both idiosyncratic and very much of its time. The subject matter in his work is interesting; sometimes highly religious, sometimes NSFW – which was Gill in a nutshell, really.

Something based on a Gill design would suit simple black line artwork best, with a little shading and perhaps with a spot of typographic red. But if a design calls for a richer palette that’s all quite possible. Today’s tattoo inks come in all sorts of colours, including bright yellows, greens, orange – even luminous and fluorescent inks. In theory, fluorescent tattoo ink could even be effectively invisible in light with no UV component, only coming to life when the right UV wavelengths fall on it. Nokia recently took this custom ink idea even further. Earlier this year it filed a patent application for vibrating tattoos that can be used as mobile call alerts. The application talks mostly about temporary sticker-style tattoos, but it does include some details of ‘ferromagnetic’ inks for putting magnetically controllable pigment into the skin, then setting the particles up ready to be activated by an incoming call. It isn’t clear whether this is ever going to see the light of day, but it sounds like an intruiging mix of cultures. And something ripe for pranking if you ever know someone with this kind of treatment.

If I do go ahead with a personal design at least there are now methods of removal that are moderately effective if I changed my mind. Lasers can be used to break down the pigment particles in the skin to small enough sizes for the body’s natural renewal process to handle. It’s something that takes multiple visits over many months, so still not a quick fix. It’s might be telling, too, that I’m thinking of these things; if I need to look so far into the details of tat removal, maybe I’m just not ready to use my skin as a sketchbook? I prefer to think that I’m just not rushing into it. I’m with Cher on this; she once said (yes, I’m quoting Cher) that ‘for someone who likes tattoos, the most precious thing is bare skin.’ And no, I won’t get an Apple tattoo, give me some credit.